ADIPS Mini Oral Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society and Society of Obstetric Medicine Australia and New Zealand Joint Scientific Meeting 2025

Retrospective Audit on Congenital Anomalies in pregnancies affected by diabetes (#208)

Background: Maternal diabetes is a well-established risk factor for fetal congenital anomalies, with risk thought to be proportional to the severity of dysglycaemia1,2,3. In Victoria, there are ~400 terminations of pregnancy per year due to major congenital anomalies4. However, the overall contribution of maternal diabetes to the rate of major congenital anomalies in Victoria is essentially unknown.

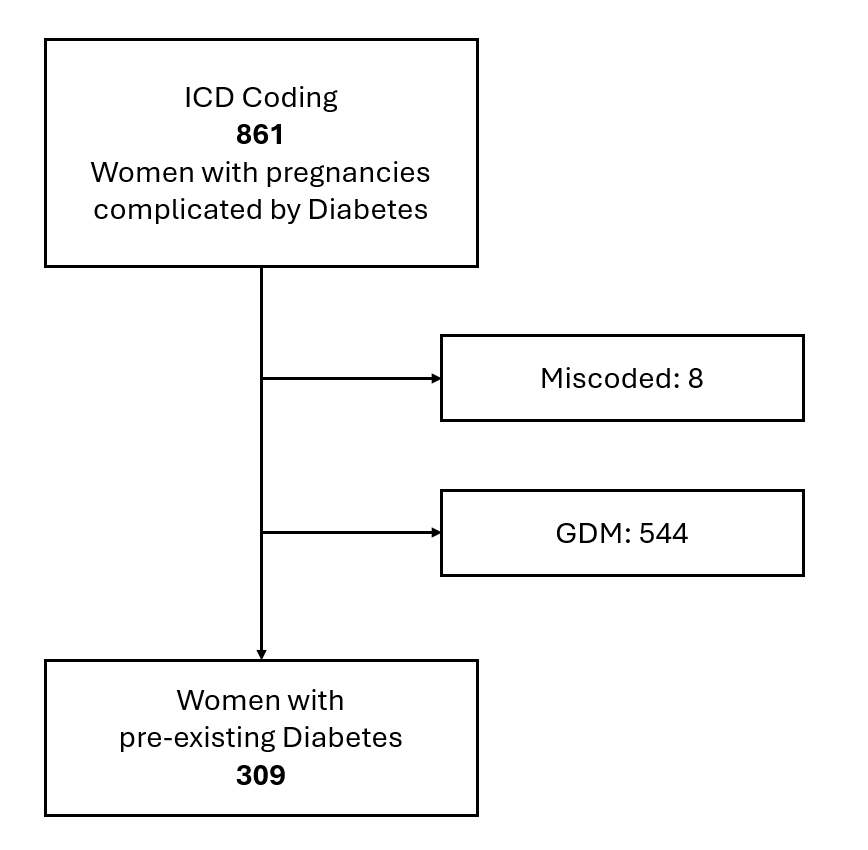

Methodology: We conducted a retrospective audit of the Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) or ‘high-risk’ service at the Royal Women’s Hospital to evaluate the prevalence of congenital anomalies in pregnancies affected by maternal diabetes. Using ICD coding, we identified 861 unique patient records coded for diabetes between August 2020 and March 2025. We included pre-existing diabetes types (T1D, T2D) and excluded GDM (Figure 1). We identified 384 mother-fetal dyads exposed to diabetes, considering each fetus in a multi-fetal pregnancy and in recurrent pregnancies. Where a fetal anomaly was identified, the medical record was reviewed to confirm the diabetes type and the congenital anomaly type.

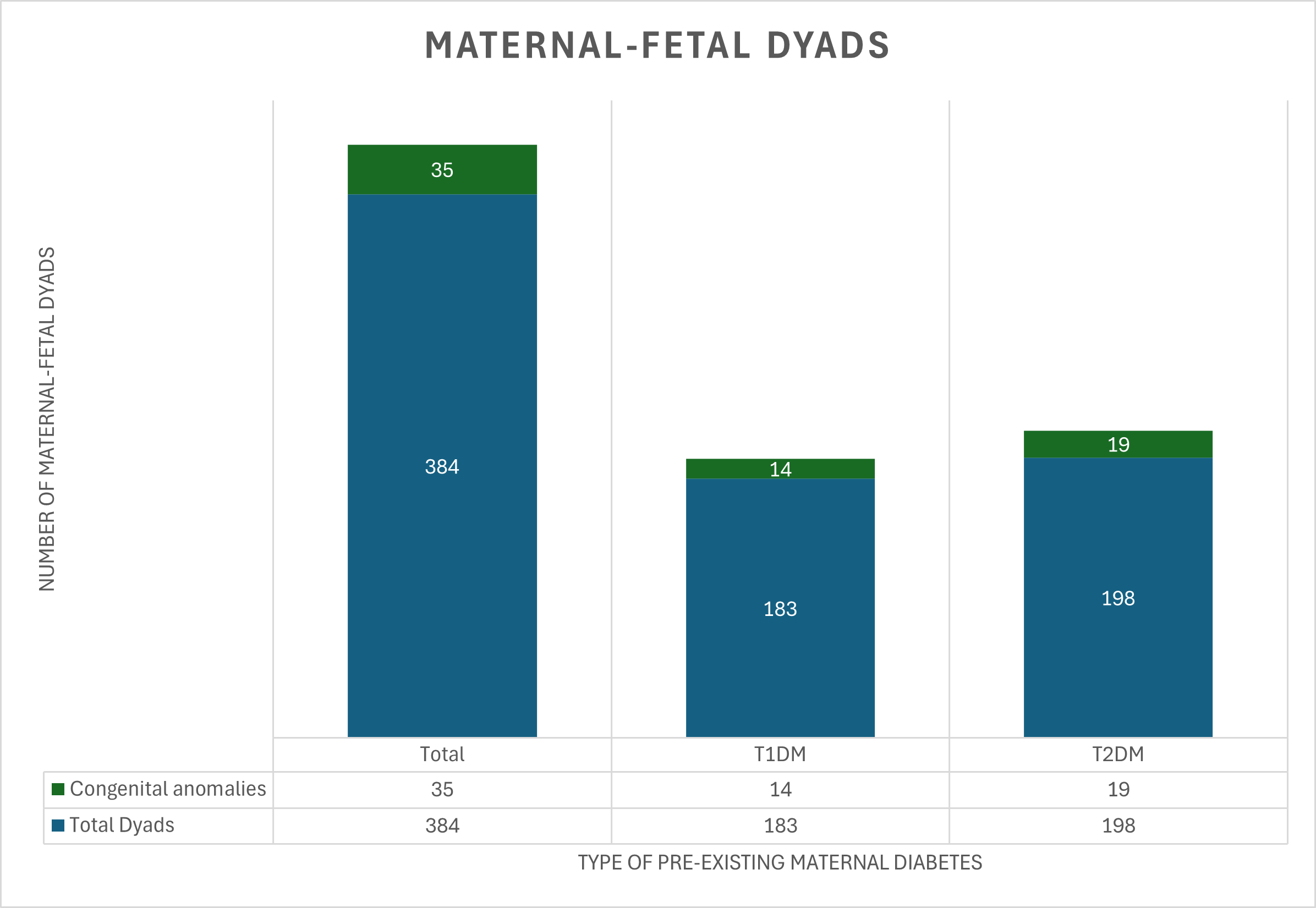

Results: Within the specified period of interest, 9.1% of diabetes exposed dyads attending the ‘high risk’ MFM service had a fetus with an identified congenital anomaly. The prevalence in Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) was 7.7% and in Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) was 9.9% (Figure 2). We plan to review these mother-fetal dyads for risk factors including first trimester HbA1c>7% and postcode reflective of socio-economic status in the lowest quintile.

Conclusion: Despite preconception counselling and antenatal care, pre-existing diabetes remains a major driver of congenital anomalies.

Figure 1

Figure 2

- Malaza, M., et al. (2022). A Systematic Review to Compare Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Pregestational Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

- Wu, Y., et al. (2020). Association of Maternal Prepregnancy Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus with Congenital Anomalies of the Newborn. Diabetes Care.

- Hanson, U., et al. (1990). Relationship between haemoglobin A1C in early type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic pregnancy and the occurrence of spontaneous abortion and fetal malformation in Sweden. Diabetologia.

- Davidson, N., et al. (2005). Influence of prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy termination of fetuses with birth defects on the perinatal mortality rate in Victoria, Australia. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology.