ADIPS Poster Presentation Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society and Society of Obstetric Medicine Australia and New Zealand Joint Scientific Meeting 2025

Sweet signals – Prenatal predictors of post-partum dysglycaemia in gestational diabetes (#136)

Background: ADIPS guidelines recommend that all women with gestational diabetes mellitus(GDM) undergo follow-up oral glucose tolerance test(OGTT) at 6-12 weeks post-partum to assess for persistent dysglycaemia.1

Aim: To identify factors associated with persistent dysglycaemia on post-partum OGTT.

Methods: We analysed prospectively collected data from 8102 singleton GDM pregnancies defined according to ADIPS19982(October 1991-February 2016) and ADIPS2014 criteria1(March 2016-April 2025). Post-partum dysglycaemia was defined as having any of impaired fasting glucose(IFG; fasting glucose 6.1-6.9mmol/L), impaired glucose tolerance(IGT; 2-hr glucose 7.8-11.0mmol/L) or diabetes(fasting glucose≥7.0mmo/L or 2-hr glucose≥11.1mmol/L or HbA1c≥6.5%) on follow-up OGTT. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with post-partum dysglycaemia.

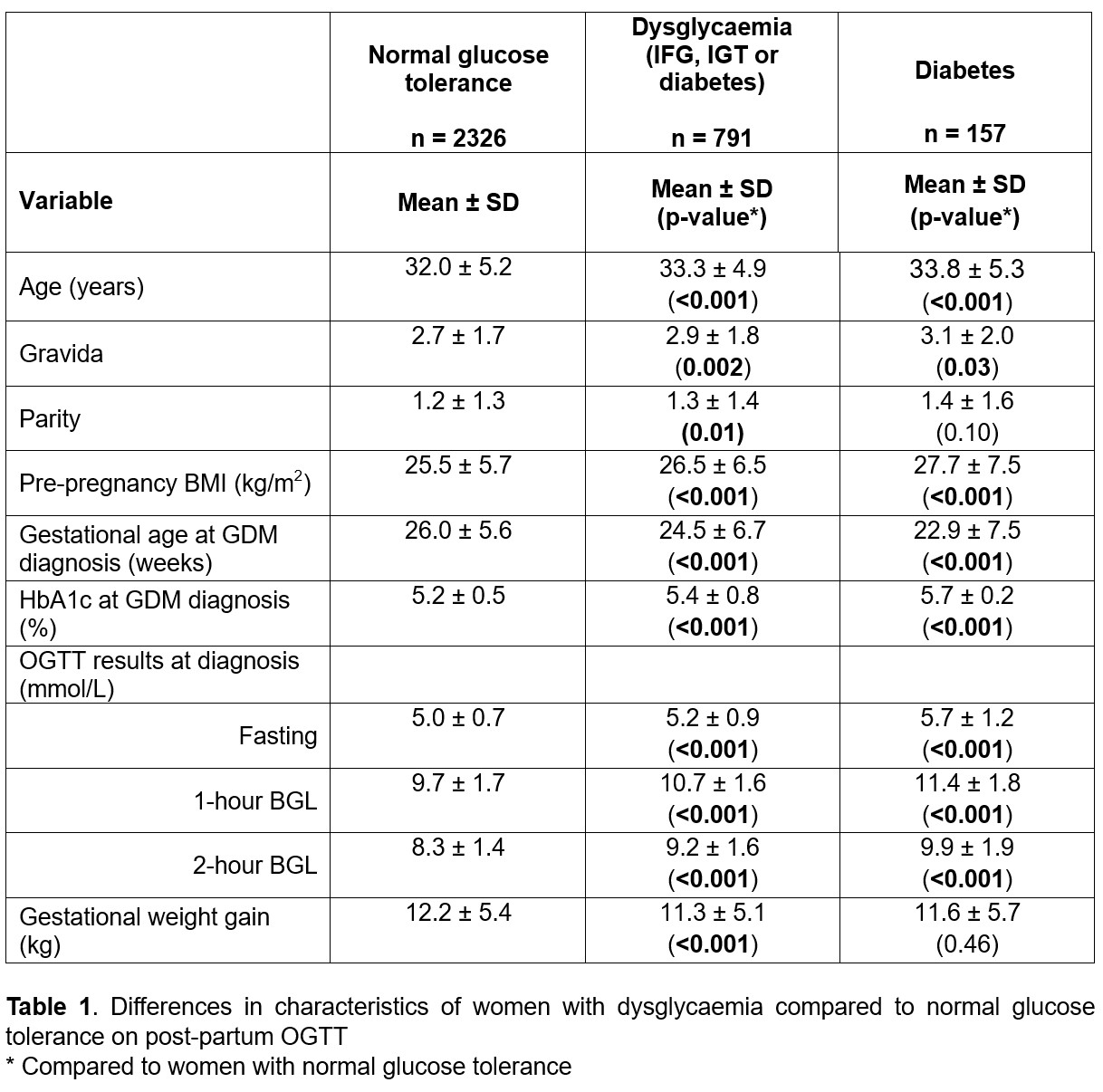

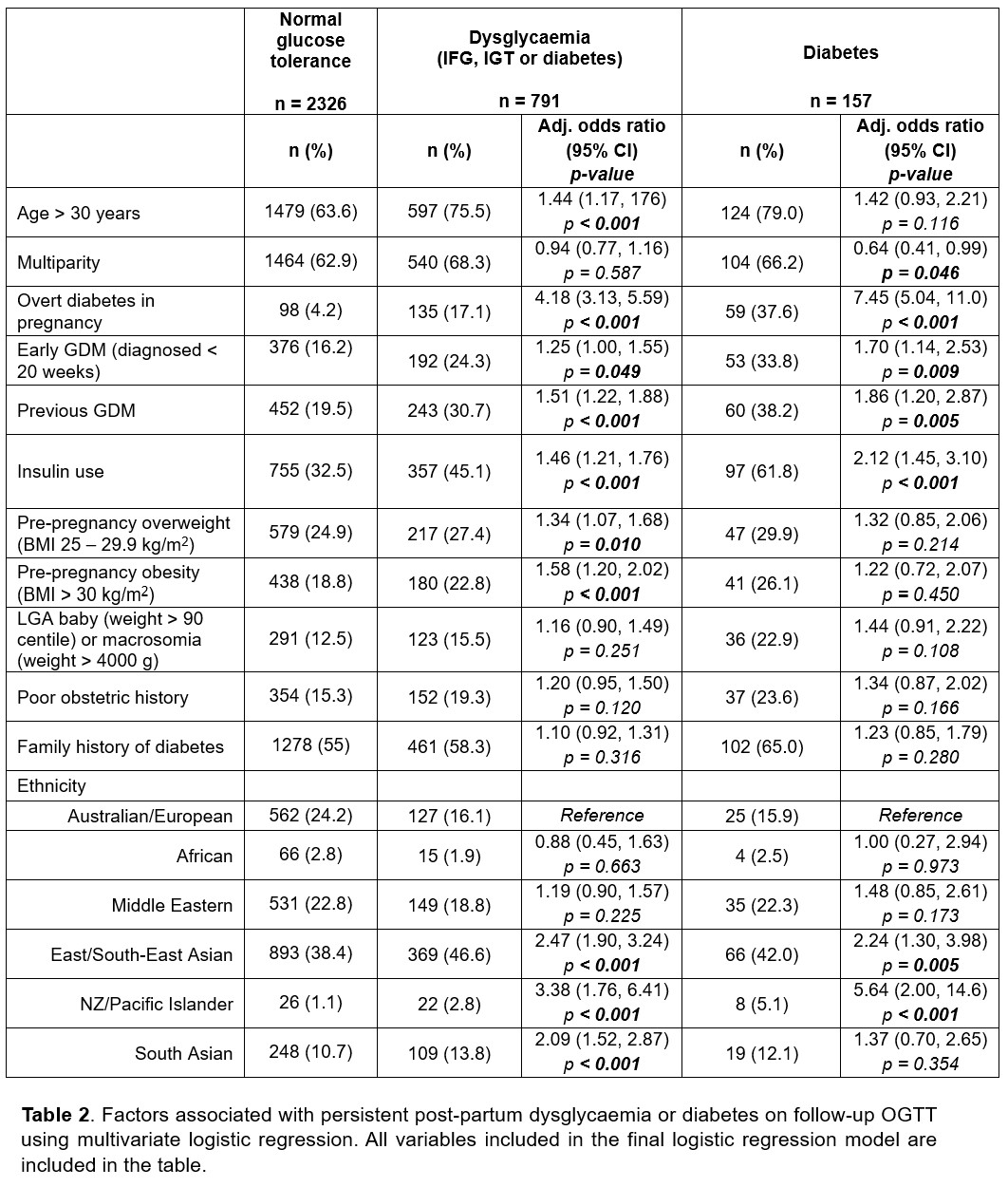

Results: A total of 3117(38.5%) woman with GDM attended follow-up OGTT. Of 791(25.3%) women with post-partum dysglycaemia, 157(5.0%) had diabetes and 634(20.3%) had IFG and/or IGT. Women with post-partum dysglycaemia were older, had higher gravida/parity, higher pre-pregnancy BMI, earlier GDM diagnosis, higher HbA1c and higher fasting/1-hour/2-hour BSL at diagnosis, and greater gestational weight gain(all p<0.001;Table 1). On multi-variable analysis, age > 30 years(p<0.001), overt diabetes in pregnancy(ODIP; p<0.001), early GDM(p=0.049), previous GDM(p<0.001), insulin use(p<0.001), pre-pregnancy overweight(p=0.010) or obese BMI(p<0.001), and East/South-East Asian, NZ/Pacific Islander and South Asian ethnicities(all p<0.001) were all independently associated with persistent post-partum dysglycaemia(Table 2).

Conclusion: In our cohort, age > 30 years, ODIP, early GDM, previous GDM, insulin use, pre-pregnancy overweight or obese BMI and East/South-East Asian, NZ/Pacific Islander and South Asian ethnicities were associated with persistent post-partum dysglycaemia. Targeted efforts at post-partum follow-up should be directed towards women with these risk factors.

- 1. Nankervis, A., McIntyre, H., Moses, R., Ross, G., Callaway, L., Porter, C., Jeffries, W., & Boorman, C. (2014). ADIPS Consensus Guidelines for the Testing and Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Australia. http://adips.org/downloads/2014adipsgdmguidelinesvjune2014finalforweb.pdf

- 2. Hoffman, L., et al., Gestational diabetes mellitus--management guidelines. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society. Med J Aust, 1998. 169(2): p. 93-7.