ADIPS Poster Presentation Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society and Society of Obstetric Medicine Australia and New Zealand Joint Scientific Meeting 2025

Title: Bridging the Gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and the general population: A Retrospective Analysis on Pregnancy Outcomes in women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (#124)

Aim: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australia (hereafter referred to as Indigenous women) experience a disproportionate burden of disease. This study aims to compare pregnancy outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Method: A retrospective analysis was conducted of epidemiological and clinical pregnancy data from Indigenous and non-Indigenous women with GDM who delivered singletons at Liverpool Hospital between April 2020 and April 2025.

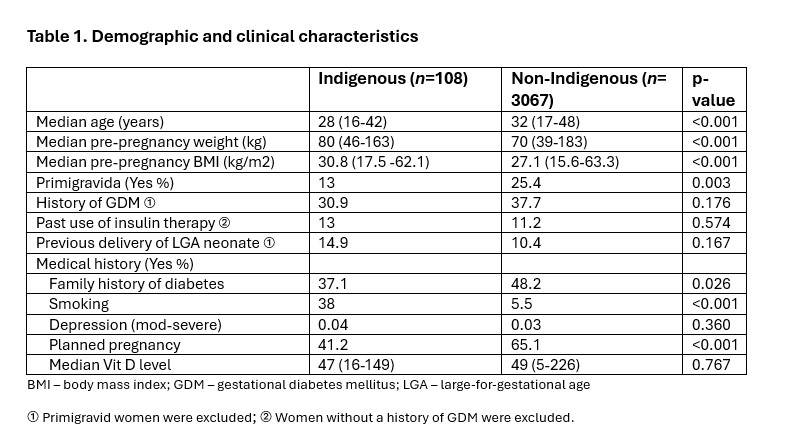

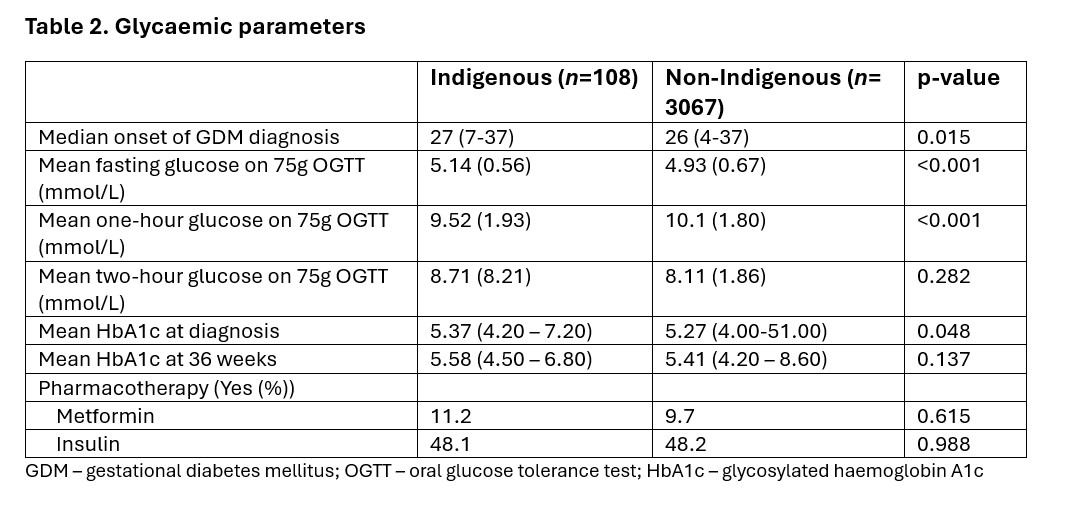

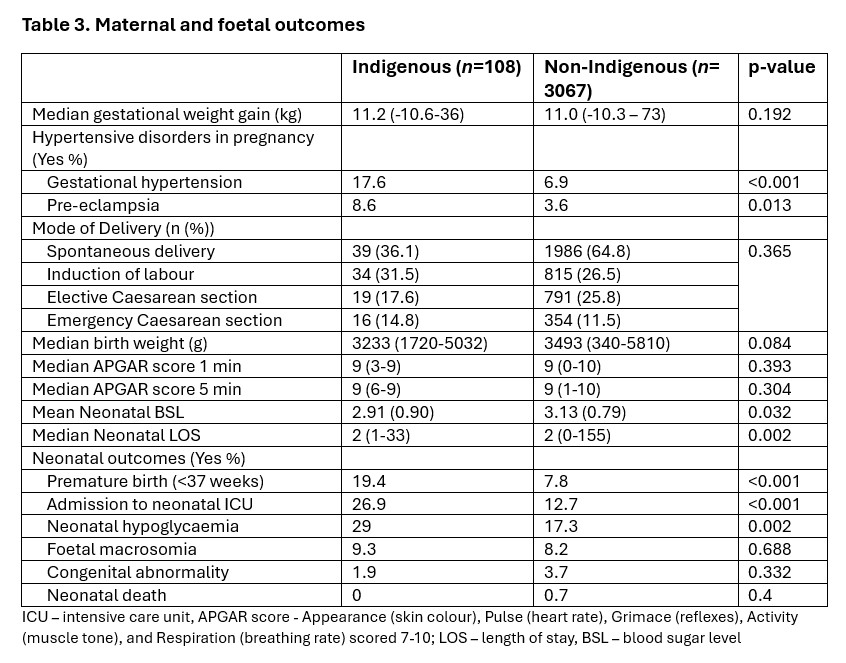

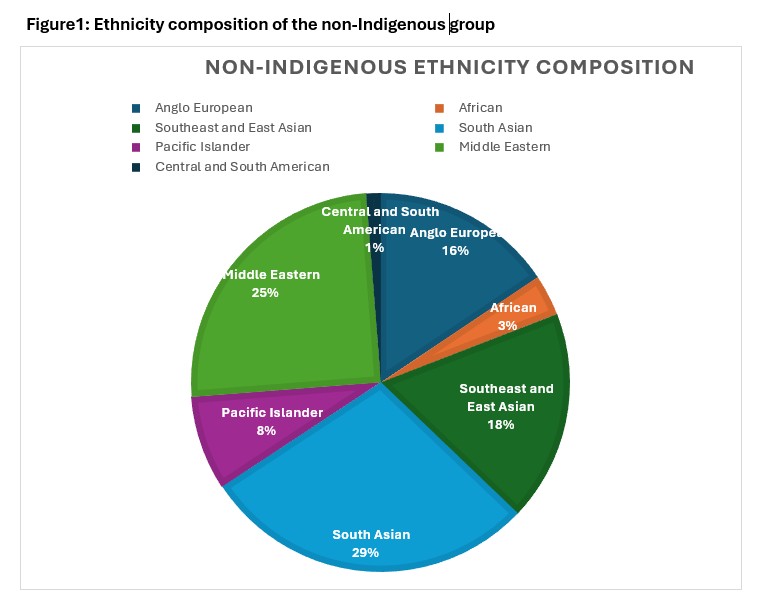

Results: Among 108 Indigenous and 3,067 non-Indigenous women, Indigenous women were younger (28 vs 32 years, p<0.001), had a higher body mass index (30.8 vs 27.1 kg/m², p<0.001), and smoking rate (38% vs 5.5%, p<0.001), but a lower reported family history of diabetes (38.1% vs 48.2%, p=0.02). They had more unplanned pregnancies (58.8% vs 34.9%, P<0.001), were diagnosed with GDM later (27 vs 26 weeks, p=0.01) and had higher fasting blood glucose levels (5.14 vs 4.93 mmol/L, p<0.001), with no significant differences in metformin or insulin use between groups. Gestational hypertension (17.6% vs 6.9%, p<0.001), pre-eclampsia (8.6% vs 3.6%, p=0.01), preterm birth (19.4% vs 7.8%, p<0.001), neonatal intensive care admissions (26.9% vs 12.7%, p<0.001), and neonatal hypoglycaemia (29% vs 17.3%, p=0.002) were more prevalent among Indigenous women compared to their counterparts.

Conclusion: Indigenous women with GDM have a higher risk metabolic profile and experience more adverse pregnancy outcomes than non-Indigenous women. Addressing these disparities requires culturally appropriate strategies that include pre-pregnancy counselling, early detection, and multidisciplinary care throughout pregnancy and the peripartum period.

- References: Voaklander B, Rowe S, Sanni O, Campbell S, Eurich D, Ospina MB. Prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy among Indigenous women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the USA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(5):e681-e98. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Diabetes: Australian facts: Australian Government 2024 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes/contents/how-common-is-diabetes/gestational-diabetes.] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021. Pregnancy and birth outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women 2016–2018. Cat. no. IHW 234. Canberra: AIHW